Foreign Insulators

by Marilyn Albers

Reprinted from "Crown Jewels of the Wire", December 1985, page 10

Don Fiene (Knoxville, TN.) is our "guest editor" this month. He is

also our expert on insulators from the USSR, and has written up the following

account of his travels to the Soviet Union in June of this year, which I would

like to share with you.

Thanks, Don, one more time, for letting the readers have a glimpse of your

insulator adventures in the Soviet Union. I reread the stories you sent in for

the June, 1981 and the September, 1984 issues, and it seems you have figured out

a few more angles since then. It might be wise if you also figured out a way to

keep those people in uniform from reading the same accounts, and I am talking

about the ones who live in the USSR!!

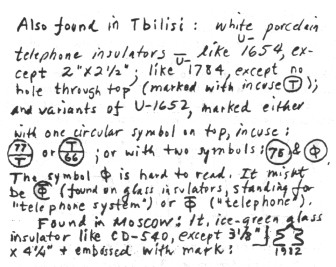

SOVIET INSULATOR REPORT, 1985

by Donald M. Fiene

From June 12th through 29th I led a group of 50 students and other tourists

on a tour of the USSR, entering at Leningrad and leaving from Moscow. From

Leningrad we flew to Yerevan, capital of the Armenian SSR; from there we went by

bus through the foothills of the Caucasus Mountains, to Tiblisi (Tiflis) capital

of the Georgian SSR, passing enroute through a portion of Azerbaijan SSR. Next

we flew to Kiev, capital of the Ukraine, thence to Moscow. I made a point of

leaving from Moscow because the customs at Leningrad has gotten very rough over

the past several years. I got a few insulators out last year but wasn't sure I

could do it again. I was hoping Moscow, especially under Gorbachew, would be

more tolerant of eccentric baggage. As it turned out, not a single person in our

group was searched upon leaving -- so I took out 23 insulators, an iron railroad

warning sign 11 x 17", several big pieces of obsidian rock, a huge Soviet

flag and sundry other contraband. And I also had my burglary tools to worry

about: large pliers, wire cutters, screw driver. All that stuff (including a

large glass insulator with much metal attached) was packed into a strong and

roomy carry-on handbag. That bag went through X-ray machines at five major

airports, both Soviet and U.S., just during the period when the Lebanon

hijacking was hot in the news, and not a single airport worker could get up

enough curiosity to search it. Makes you wonder, don't it?

Of the 23 insulators,

8 were small (1" or less) porcelain knobs and the like; of the remainder,

all but four were relatively uninteresting porcelain pin-type; and out of the

lot there was only one undamaged glass pin type -- and that was a duplicate for me

except for color and embossing. So, despite the fact that I was able to consider

12 pieces new (more or less) to my collection, I cannot say this was a brilliant

haul. But I had a ball depriving the Russians (and other Soviet nationalities)

of all that junk. So I'm happy.

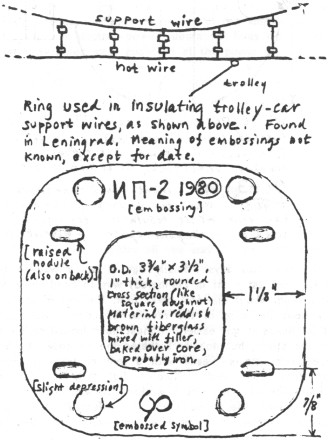

We arrived in Leningrad early evening in a light

rain. From my hotel window I could see some interesting construction about a

block away. Around 10 p.m., over the protests of my wife, I went out to

investigate, carrying my tools in a plastic bag. I found a side street with

buildings coming down on one side and going up on another. All the trolley-wire

poles had had to be relocated over one long block. Old poles and wires lay in a

tangled mass along one side of the street. I could see hundreds of insulators,

but all except three of four were tightly tied into long lengths of 3/16"

iron wire that my cutters could not touch. I finally got one special type of

insulator, used in the support-wire system, unbolted from two metal straps. It

was reddish-brown in color and shaped like a sort of square doughnut (see

drawing), apparently consisting of fiber glass and plastic baked over a core,

possibly of iron.

It took a lot of cursing to get the rusted bolts loose, but

none of the people standing around waiting for trolley cars in the rain seemed

to mind. They could see me very well, of course, because even at midnight under

clouds there was full visibility.

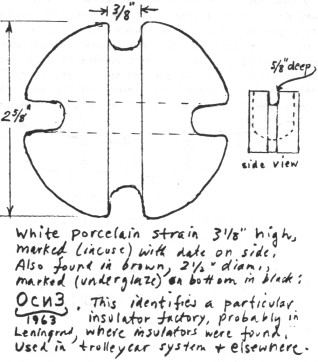

I picked up a couple of loose pin-type

porcelain insulators and one unattached strain. There were several nice strains

that I craved, but lengths of thick wire up to ten feet long dangled from either

end. I finally gave up and went home. My wife was glad to see me. (In general,

throughout the trip, I had much more difficulty getting permission from my wife

to go insulator hunting than from any Soviet official.)

Over the next two days I

finally figured out a way to get the strains. What I did (on our last night in

Leningrad) was to bend those long wires over my knee at a point about one foot

away from the end of the insulator. Then I laboriously bent the wire in the

reverse direction. And then back again. After about 50 bends it got easier. I

must have looked rather odd doing that out there in the street, but nobody

bothered me. I ended up after an hour or so with three nice strains -- each with a

foot of tough jagged wire sticking straight out from either end. Nice -- but they

would never fit in my handbag. Early the next morning I worked my way down into

the bowels of the hotel and found the dispatcher. I confessed to being an

American insulator collector, showed him my wired-up strains, and told him I

needed a hacksaw bad. He practically leaped up from his bank of switches and TV

monitors, personally guided me down yet another floor to the repair shop, where

he abruptly woke some poor devil sleeping on a table, introduced me, and split.

The new guy appeared to adore all Americans, nearly went crazy trying to find

his hacksaw. Finally he gave up and instead used an electric grinding wheel to

cut away the wires. In his zeal he burned the heck out of his hands as he pulled

away the red-hot metal. I thanked him profusely and gave him some souvenirs for

his two kids -- ballpoint pens and a handful of U.S. Army patches that I had

picked up at a flea market in anticipation of just such occasions. As I boarded

the plane for Yerevan, I carried with me four porcelain pin-type, four strains,

and the "square doughnut."

Our three days in Yerevan, far to the

south, were fascinating, but I found no insulators. Usually I would try to take

long walks near sunset (like about 9 p.m.) in the alleys and courtyards near our

downtown hotel. At the rear of almost every apartment building grapevines had

been planted. At ground level they filled massive trellises, and from there they

climbed upward from balcony to balcony. The older the building, the higher the

vines. Among their leaves I spied many a dormant insulator, but they were all

too high to reach.

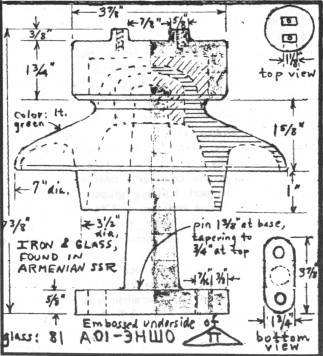

Not till our bus ride north did I acquire my first (and only)

Armenian insulator. We stopped near Lake Sevan for lunch. I took a quick walk

along a railroad track, where I picked up a smallish iron warning sign that I

decided to keep: roughly pennant-shaped with vertical red and white stripes. In

the distance I could see an electric-power substation; lines fanned out from it

into the mountains. The lines were anchored at the power station with a dozen or

more "sombrero"-type glass insulators -- ice-blue and sparkling in the

sun. Long before I reached the station, I encountered two ten-year-old Armenian

boys. They spoke Russian perfectly, having learned it at school. I asked them if

they had seen any discarded insulators in the grass thereabouts. They hadn't. I

gave them each a dime (which they at first refused to take, having been raised

by their mothers to be polite) and asked them to hunt for insulator -- and if they

found any, to "meet me at that red bus over there in about thirty

minutes."

When I finished lunch, the boys were waiting for me. They had

asked the manager of the power station to help me out -- and he had said he would.

I felt almost faint from greed. I told the bus driver to pick me up at the road

leading off to the substation; he said they were leaving in ten minutes. The

boys and I ran cross-country all the way to the mother lode. I quickly

introduced myself to the station manager, who had been playing dominoes in a

comfortable little shack with his two helpers. (Easy work.) I showed the guy

some photographs of my collection, but he needed no such convincing. He thought

collecting insulators was an eminently sane hobby. As we walked out the door, he

said I could have any insulators I found. He took me to one pile of same in some

weeds, but there wasn't a single piece in it that weighed less than forty

pounds. Darn. Finally we found just one item light enough for me to carry -- the

glass-and-metal insulator described in the attached drawing. I had noticed these

on poles form the bus window -- as many as six or nine in a single installation. A

lot of connecting metal, perhaps switches, had been fastened to their tops.

Possibly there were fuses as well, each installation acting as a lightning

arrester. The iron metal on the insulator had been covered with aluminum paint.

Rust was showing through.

I told the manager I had to rush off, but "thanks

a lot just the same." He was really disappointed; he wanted to give me

everything he had. "It would be nice to have one of those,” I said,

pointing to the sombreros high overhead. "Hey,” he said. "You can

have one. But it will take me an hour to get it down for you." "No

time,” I said. "Gotta go..."

The boys and I jogged over to the bus.

Before I boarded, I tried to give the kids more presents -- coins, pens and army

patches. They refused to take anything, held their hands behind them. So I

carefully laid the stuff on the grass at their feet, thanked them, and hopped on

the bus. As we pulled away, I saw the boys pick up their presents. They looked

happy. But it was clear their greatest reward had been to act as intermediaries

in an important international transaction. And I was not only happy, but amazed

to think that the manager had been willing to cut off the power to half of

Armenia just to add one insulator to my collection, -- and also, of course, to

promote world peace...

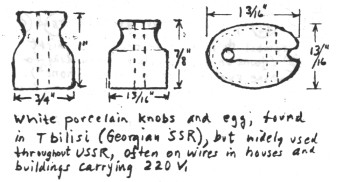

Tbilisi is a charming city of narrow cobblestone streets

laid out on steep hills. As in Yerevan, I saw plenty of insulators on the sides

of buildings but could not get to them. I hated to give up, though. On our last

morning we had one free hour before departure to the airport. I talked my wife

into taking "a little walk" with me. We climbed up a steep and narrow

street, past a Russian Orthodox church, until we came to an open place

overlooking the whole city. As we stood there admiring the view, I noticed a

couple of workmen off to the side. I approached the older of the two. I asked

him if he knew where I could put my hands on some insulators. I told him I was

an American, etc. His face lit up. He guided my wife and me through a small

orchard to a kind of storehouse where all his tools were kept. Some stairs led

up to a small clean room with a table and a couple of chairs, where we were told

to wait. Soon the man returned with an assortment of ten insulators (most of

them small knobs). One was cemented to an iron bracket. The man thoughtfully

sawed it off just at the base. We talked a bit.

The man turned out to be 70

years old, though he looked only 50. (He was perhaps a potential example of

those Georgians who live to the age of 130 years by daily eating yogurt and

running up and down the Caucasus Mountains.) He said he had fought in the war

against Finland in 1940, was wounded; he didn't think that was a very worthwhile

war. I told him I had fought in the Korean War and didn't think it was very

worthwhile either. The man took a bottle of cognac out of a drawer and poured

three glasses. "To world peace!" I said. We all drank to it. He

refilled the glasses. "To communism and religion!" he said. We all

drank to that, too. And then Judy and I split. We made it back with one minute

to spare.

It was hard to believe that my luggage rang no alarm bells, neither in

the Tbilisi airport nor the one in Kiev, the next city we visited. I found no

insulators during our three days in the Ukrainian SSR, but the five days in

Moscow yielded a little something. Our hotel there was the Rossiya, once the

largest in the world; it is right next to St. Basil's Cathedral on Red Square --

and directly across the Moscow River from a big old power plant erected

during the Stalin years. It took me most of a morning to explore the alleys and

trash heaps surrounding the plant, which I had heard was gradually being phased

out, but I found nothing and saw nothing worth a second glance. After finally

making a complete circle of the area (maybe 20 city blocks), I saw a repair van

of some kind parked in front of the building. Sticking out of the roof of the

van was a two-pin post carrying two glass power insulators (see drawing). I went

up to the driver and went through my routine, ending with the insulator photos.

"So, Ivan, what do you think?" I said. "Why don't you just give

me these glass babies? You can replace them with porcelain later."

"Sure,” he said. "Why not?" Quicker than a flash he scrambled

onto the hood, then the roof, unscrewed both insulators and tossed them down to

me one at a time. By then the driver's two helpers had showed up. I gave all

three a handful each of pins, pens and patches -- a highly successful

international trade deal.

Now I got the bright idea to get permission from one

of the power-plant executives to hunt for insulators inside the grounds. So I

went into the main building and told my story to a reasonably sympathetic woman

guard doing duty in the lobby. She pointed to a chair and told me to wait. She

returned after 30 minutes with the information that no one there had the

authority to give me the permission I sought; I would have to apply to the

Ministry of Electrification on the Kremlin side of the river. The woman in the

lobby of the ministry gave me several phone numbers to try. It took me two hours

of telephoning, both from the lobby and my hotel room, to reach the most

promising name on my ever-growing list of "people to try." But this

person seemed almost shocked by my intention of collecting Soviet insulators.

"Who gave you my name? Who gave you my name?" He kept demanding.

"The woman in the lobby,” I kept shouting. (It was a bad connection.)

Finally I hung up on the creep. But next year I'll try to crack that bureaucracy

again, and I won't rest until I have a letter authorizing me to request

discarded insulators from power plants, substations and the like. Let it be an

innocuous letter, just so long as it is written on official stationery from the

Ministry of Electrification.

And think of how valuable such a letter would be at

customs! This year I got lucky and wasn't even searched. But next year some

gorilla might arrest me and make me miss my plane. However, with a letter from

the Ministry mentioning both me and insulators in a positive context, I would

have it made in the shade. And the letter would almost certainly work the

following year, too. Who knows, it might even get me through Soviet customs for

the rest of my life!

|